14 January 2015:

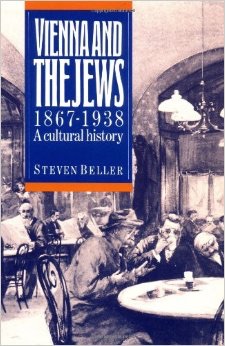

Why have I read this book? You tell me! I watched my favourite TV-channel one day, which is Axess, and came straight in to a discussion forum, about Jews and Vienna. It was fascinating and I made a point at not missing the next forum, which had this Steven Beller, as a guest among others. Let’s say, I thought the book would be more like the forum or seminar, than what it turned out to be.

One problem with writing a book like this one must be, that it fuels anti-Semitism. When looking at statistics, which the entire first 72 pages, are made up of, the author separates the Jews from the rest of society. As a group of their own, who doesn’t really belong. And is this not what all these jews were striving for, in Vienna, to be part, to be allowed to go in to every single career they might be interested in? Society blocked them from choosing whatever career they wanted though. They were not allowed in the bureaucracy at all, they could not hold government jobs, because of anti-Semitism, so they were basically forced to become doctors and lawyers. And to me, it is sad to see that their options were so limited and people in their anti-Semitism, declaring that they chose those professions because they wanted to go in to them and earn a lot of money. That was not true though.

A book like this very much creates an us and them. Especially since the author wants to count in Jews who long ago had abandoned everything Jewish. Converts are counted as Jews and maybe they would highly have objected to be called such? And how about the ones who had been totally assimilated by generations? To have a Jewish ancestor 200 years earlier doesn’t make you automatically Jewish, unless you adhere to the Nazi ideology. If you reason Jewish descent makes you Jewish, well then we are all Jews aren’t we because we all stem out of Adam and Eve. In other words, the author takes this too far.

The first 72 pages goes through all Jews involved in the fin de siècle around the turn of the century 1900, whether they indeed were Jewish or had Jewish sounding names. Not too interesting in my point, since I am not that much for speculation. But the latter part of the 72 pages, does bring up the interesting fact that Jews rarely were part of the working class in Vienna and that the Gymnasiums were full of Jewish students preparing themselves for a University education. (Realschule did not give a student access to University.) Most of them having merchants for fathers, but instead of choosing business for profession, they opted for medicine. Sigmund Freud was a very typical young man in that respect. These statistics also makes your mind wander because when the Nazis forbade Jewish children to attend schools, it meant that many schools stood more than half empty!

Jews have through the ages been encouraged to study in a completely different way than other religions. From the beginning it was studying the Torah and then the Talmud in Yeshivas. But the more assimilated they became, or should I say, the more enlightened they became, the more the studies moved over to worldly subjects. The ultra orthodox do not study worldly subjects but count on others doing so, especially non-orthodox jews, so they can draw advantage of that. Like going to the doctor…

This book is deep, very deep and many things which the author brings up, is just not within my scope to understand, no matter how many times I re-read the difficult paragraphs. This is not the sort of book you read in an afternoon and while I usually read all footnotes in books, I have skipped them in this book. Enough is enough, the bread text was tough enough. Below I will try to sort out what the book might be trying to say.

When the author starts getting in to the topic which the book is supposed to be about, it is not straightforward at all. A lot is assumptions and speculations, but what else can there be when one is trying to understand a world one did not live in oneself and people living in it, not recording their feelings. Even if they had, an ethnologist will always interpret this as the person not really knowing what they are all about. One does never see oneself as molded by one’s culture. Beller’s first question is about the Viennese Jews having a Jewish consciousness or not. He claims that they did because if you say that you don’t follow the religion, that you don’t know anything about it or its culture and traditions, then you know that there is a problem with being Jewish and admitting it. You have thought through the problem and have decided what to do, say and what sort of defense to put up. In that you have admitted that you are Jewish after all since a non-Jew would not even think about these things. And why was it a problem with being Jewish in 1895 and onwards? Because Vienna was the hot-pot for anti-Semitism. The political party in power was highly anti-Semitic, Vienna was the birth place for Zionism and this was the city where Hitler learned to hate the Jews! And even if you denied being Jewish at all, others regarded you as such which was noticeable among other things, when you did not get promoted.

The author does make a difference between Jewish consciousness in that there was positive and negative consciousness. To say that “noone regarded me as Jewish” before 1938, is deemed negative consciousness. The person Käthe

Käthe Leichter who died 1942 in Ravensbrück Concentration Camp. Käthe, they DID KNOW that you were Jewish!

Leichter, left-wing socialist, was proud of the fact that noone took her for a Jew. When indeed that was not the case at all, had she looked closer at her colleagues and so-called friends. And is this not the cause for so many Jews staying on in European countries, even after Hitler started persecuting them? They denied the truth. That they thought that their neighbours did not regard them as Jews, when indeed they did. When anti-Semitism was not politically incorrect, the people showed their true feelings. And it came as a shock to the assimilated Jews who had not seen themselves as a “problem”. The author claims that being proud of mistakenly being taken for an Aryan, is very much a sign of Jewish consciousness but of a “rather odd kind”.

The book is really supposed to be about if the Jewishness had any effect on the culture in Vienna. Were Jews more open to new things because of a mythical Jewish mind? The myth says that Jews are better abstract thinkers than others, which makes them for example better mathematicians. The author then points out that Jews were really underrepresented in the world of mathematics. He points out that one can never draw such a conclusion and points out that not only is every person its own individual but the fact that Westjuden were very much different from Ostjuden, points against all this talk. That this sort of talk is just plain anti-Semitic and that it makes the things feared the most, in to Jewish traits. Is abstract thinking feared though? I was surprised that he did not add, that Jews studying the Torah and Talmud, not only read them but discuss them, and in that respect, they are used to abstract thinking, compared to someone who does not study in that way. Honstly, everything concerning religion is abstract! That is why my autistic boys don’t understand anything in church!

How Jewish were the cultural élite in Vienna? Beller points out that there was almost always three generations between anything remotely orthodox and the turn-of-the century Jews in Vienna. Had they not given up the specifically Jewish ways of life and thinking, they could not have participated at all in the culture around them. Most looked at Judaism with indifference. While some could feel that conversion was a betrayal to their family’s history, it often happened upon marriage. And children were brought up as Christians. Others who remained Jews, were not really upholding the traditions. Beller points out how people complained that children no longer understood Hebrew and that they looked upon Bar Mitzvah as a present receiving event. He brings up Freud throughout the book, since he is a classic example of the Viennese Jew. His father was a merchant, and as most merchant sons, he was sent to Gymnasium so that he could become a doctor or lawyer instead. His father studied Talmud but only some people claim that Freud has Talmudic ideas in his discourses. Beller agrees that sure, Talmud says that one should study symbols in levels, but that does not prove that Sigmund Freud studied Talmud and Kabbalah.

One very, very interesting aspect brought up in the 7th chapter, is the aspect of education which of course is a precursor to all knowledge and interest in culture. And there is proof of that the Jews have regarded education as more important, than other groups. Beller thinks that it stems from the destruction of the Temple and it does make sense. In the Temple, the Jews worshipped God but after the destruction of the Temple, their worship had to change form. It had to take the shape of studying the Scriptures instead and it became every Jew’s duty to do so. This would make the entire people of Israel a “kingdom of priests”. The place for worship became: The schul (school really) or synagogue, where the Rabbi became the teacher, not a priest. The perfect man was one who was versed in the Law after studying the Talmud. So no matter how poor parents were, they scraped together money to send their three-year-old sons to Cheder where they would learn to read and write Hebrew. The little boy had to sit still and translate difficult texts of Hebrew while the Christian children did not start school until the age of six or seven and they were very slowly taught how to read their own language.

Of course there were reasons for these differences and not just the reason of Jews being commanded to study the Torah and Talmud. Most Catholics in Austria were peasants and their children were needed in the fields and on the farms while the Jewish children always had merchants for parents. But the religion also did play a big part in why Catholic children did not go to school. You only needed to do so if you were going to become a priest and the church itself did not want the masses to learn too much. Only the élite, the clergy, would preach the doctrine, and the population should accept their lot and religion. On the other hand, Jewish children only received religious education and were not involved at all with the secular world. Traditional Jews were hostile to secular learning. But not all over. Not in Bohemia and not in Hungary. In the late 1700s, the Jewish Enlightenment took place, called the Haskalah. The inspirer was Moses Mendelssohn. To him and all the rest of the Maskilim (followers of Haskalah) Judaism was revealed Law, not truth. Faith could only come through the study of the world. They saw it as a necessary aid to religious knowledge. While Christians feared the scientific revelations of how things worked, the Maskilim saw all discoveries as further evidence of God’s ways. For many Jews, secular learning after this became a substitute for religious learning and it inherited the latter’s prestige. Jews would look down on people who learned nothing, studied nothing, but a medical student was held in as much esteem as a religious Torah student. The emphasis on learning, is what the assimilated Jews brought to Western culture. The goal remains the same for all scholars, the pursuit of knowledge, is really the pursuit of faith. Or as Moses Mendelssohn claimed: Faith is taught “at all times through nature and things, never through words or written signs”.

What really came as news to Jews, was the aesthetic world. They were not used to look for beauty in the world, it was never discussed among them before. This is where Beller starts discussing the salon phenomena of Vienna. In aristocratic circles it had been a place to be seen, a social place where you associated with your class and listened to music. But the Jewish salons were something else. Hosted by Jewish women, they were a refuge for cultured people to meet and discuss, to be understood and encouraged, as Beller says. The emphasis was on your education, not the class you had been born in to. In a sense it was the traditional Jewish learning place, but not for religion but culture.

Jewish families did not send their young children to Cheder to learn Hebrew anymore, but they kept starting their children’s education at an early age. And they wanted their children to get a better education than themselves. Education made you accepted and assimilated. But education also made it possible to move out of the merchant class, since it opened up for choices. But it was not only a way to enter society and climb the social ladder. Many, many studied for its own rewards, for the gaining of knowledge. They did not care if noone read their books or if they did not get promoted. Education was no sure mean to get somewhere either, since the military and bureaucracy, was closed to the Jews no matter what. The cultural Vienna that is spoken of today, that was such a remarkable thing around 1900, was in other words not at all the aristocratic Kultur as Beller says, but the Bildung one. The educated culture or perhaps one should call it “the religion of learning”? Being obsessed about gaining knowledge? What the Viennese Jews did, the ones involved in this culture, was that they were wholly totally dedicated “to the world of ideas and creativity”.

In chapter 8, the going gets tough when one tries to follow Beller in his reasoning and fancy words used by who else than himself? He points out that behind the emphasis on education lays a deeper thought and that being, the responsibility of the individual for his own actions. Sure, protestants have this too, but Austria was not protestant, far from it. The message the Catholic church sent out with their powerful buildings was, submit to authority and the glory of it. In this respect, the Jews did not fit in at all. Authority in their world was not coming through paintings and stone, they were even forbidden to have pictures of God by religion, because it can lead to idolatry. Authority came through the word in the book above books. Their neighbours submitted to the authority of the pope and a long line of intermediaries, their independence was limited and they were absolved from responsibility for their actions. The Jewish religion of course being totally the opposite where every man was expected to know the law and the rabbi only being a paid teacher. His knowledge could be challenged. There was lots of room for personal interpretation.

So far so good, nothing strange with those ideas. How does one fit it in to the topic of the book though? Beller continues with talking about the community of the ghetto and shtetl. It is an interesting fact to see that there was never an upper class or a proletariat. All where in commerce, according to Beller. That the difference between people was how much money they had. And even the poorest tried to uphold their “bourgeois way of life” by sending their little boys to Cheder. One’s fate was in one’s own hands. He says it is a socialist view of things but in my view, is that not what capitalism is all about. Don’t cry over your situation but do something about it? Anyway, to fit things in to his theories, he brings up the town where noone ever starved to death because when someone was poor and hungry and asked for bread, you had to give it. But one day, a man had died of starvation and people ran to the rabbi for answers. He said the man did not die of starvation. Why? He never asked anyone for bread, because he was too proud to stoop that low. He died of pride, according to the rabbi, and the people in the town could feel good about themselves.

There was a strong community feeling, all for one and one for all. And these Talmudic teachings followed people in to the salons of 1900 Vienna. The richer helping the poor. From there the step was easy to take, in to social reformation or Marxism. Some double-standards emerged from this of course. The people who grew up in rich families and who lived the life-style of the rich, at the same time started radical newspapers who demanded reforms and they employed people at these newspapers, who believed in biblical justice for all. In other words socialism. Some took a stoic attitude to everything around them, and this is when Beller really makes no sense. Sure, I can understand some of what he is saying. People living in a chaotic world, where they could not agree with employees being abused, living under tyranny. But at the same time, they did not want the world to be turned over in a revolution. They could spit on the aristocrats shortcomings and travel in third class on the train, to make a point, but at the same time not fundamentally changing. Right. I just felt that he was going further and further away from the topic and it got worse. He talks of Jews deciding that God is conscience and if you chose to not believe in God, than you could just change that sentence to there is something good in every man.

From there he moves on to the Jewish stoicism and I did not really understand what he really wanted to say here either. That we shall not fear any other man because we are all created in God’s image and therefore all faces we look in to is God’s basically. When God is unjust, he is still God, and when we then rebel against him because he has been unfair, it is just because we feel a need to have him as a friend again. The Jewish stoicism is all about wrestling with this fate that he has decreed on us, but that he is ultimately a good friend. When Jews are persecuted and insulted, they stand up on high with God and look down on it all, knowing that they have nothing but their relationship with him and that everything else is pointless. All persecution has led to that they need compensation somehow. The only meaningful thing to do in this life is to search for the true understanding of God and his laws. If you are going to be worthy of being the chosen one, you must be righteous. Maybe all this makes sense to a Jew? Personally I believe that God is my heavenly father and he does no try to be complicated. His children are supposed to understand him. But we might not like all his plans for us. What we need to learn here on Earth is to accept his will, that he knows what is best for us.

But back to the book. Not all delved in to studying the holy book but instead studied God’s creation to get closer to him, to find out the meaning of life and they were the ones who came up with the conclusion that he is conscience. The Jewish traditions, ritual laws and customs were abandoned for a more personal relationship with God. They were seen as just empty, a shell. The secularized Jewish stoicism was all about seeking one’s own mission, a faith built on conscience and “to not bow to any man or seek any man’s favour”. To be honest and true in everything. The prayer-book was replaced by a book of science. Like Freud said, do not leave anything out just because it is unpleasant to say. Truth-seeking was the motto of the day. I know, it all sounds great right and weird in certain ways and it is beyond me, why Beller has this discussion in the book! I feel like when I was studying Kabbalah in my Judaism course at University. What is the point of this???? What is it that I am supposed to understand????

Next, Beller digs deeper in to what the Enlightenment meant for the Jews. While before it, the Jews had been kept in ghettos, by laws of the states they were living in, the Enlightenment basically meant that they now where free to go live wherever they wanted to and in what ever fashion they wanted to, as well. Which was a big problem if one wanted to remain close to the Jewish religion. The ghetto not only cut the Jews off from the rest of society, it also cut society off from interfering with the Jewish culture, religion and customs. The Enlightenment which wanted to do away with all old superstitions was a serious threat, but one which many Jews welcomed. To have rights as a citizen, one was also supposed to fulfill duties and one of them being, to become as German as possible, fit in and find truth instead of relying on revealed truth. Humanity was the new religion and to become totally emancipated in this new liberal society, one had to assimilate. This was done by education.

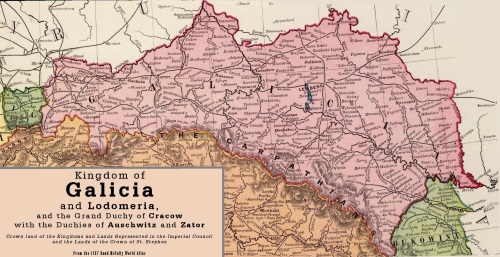

Moses Mendelssohn and his Maskilim, hated the ghettos and shtetls they came from. More and more people left and it was up to the individual to decide how accepting he should be. Go to the theater? Study German instead of Hebrew? They still accepted God but felt that all religions are good since they try to teach people to be good. Ceremonies were unimportant though. They also wanted to remain Jews, since it obviously was God’s will that they were Jews and also so that they could educate and protect those of their people, who chose to remain superstitious and clinging to old customs and traditions. The Hasidim, ultra-orthodox today, were considered their main enemies, since they threatened the understanding that was growing between Jew and Christian. To fight the narrow-mindedness of the Hasidim, Joseph Erlich in Galicia, which was a Jewish hot-pot, set up schools who would be modern but respect Judaism, like keeping the Sabbath. Poor children were

Moses Mendelssohn and his Maskilim, hated the ghettos and shtetls they came from. More and more people left and it was up to the individual to decide how accepting he should be. Go to the theater? Study German instead of Hebrew? They still accepted God but felt that all religions are good since they try to teach people to be good. Ceremonies were unimportant though. They also wanted to remain Jews, since it obviously was God’s will that they were Jews and also so that they could educate and protect those of their people, who chose to remain superstitious and clinging to old customs and traditions. The Hasidim, ultra-orthodox today, were considered their main enemies, since they threatened the understanding that was growing between Jew and Christian. To fight the narrow-mindedness of the Hasidim, Joseph Erlich in Galicia, which was a Jewish hot-pot, set up schools who would be modern but respect Judaism, like keeping the Sabbath. Poor children were provided with free clothes and shoes as an incitement. In the schools the pupils received traditional teaching but little by little things were introduced to them like maps on the walls, to show that there actually was a world outside the Hasidic world and ghetto. The goal was to make Judaism into just moral education. The Westjuden became those who stood for enlightenment and progress and the Ostjuden were all the Hasidim, going backwards and refusing to be part of the rest of the population’s cultural life.

provided with free clothes and shoes as an incitement. In the schools the pupils received traditional teaching but little by little things were introduced to them like maps on the walls, to show that there actually was a world outside the Hasidic world and ghetto. The goal was to make Judaism into just moral education. The Westjuden became those who stood for enlightenment and progress and the Ostjuden were all the Hasidim, going backwards and refusing to be part of the rest of the population’s cultural life.

The new idea that would finally join the Jews with the rest of society, was the idea of Mensch which means Human being. The first thing Jews in Austria had to do, was accept that Austria was home and not Jerusalem. Then they would be regarded as human beings and nothing else. No religion or social class would matter. If the rights of Man was the only thing that mattered, all religions could co-exist. The new idea was that religion was a private matter, something to do in one’s home and not in public. What mattered was the moral goodness of the individual, so many abandoned religion all together, the aim being to destroy a separate Jewish identity. Feeling that religion and the idea of Mensch could not co-exist. What some did was to bring with them the heritage that could be divorced from the traditions. Like the social and economic structure of the Jewish community. They had never needed drinking laws and orphanages fo example, so they were more prepared for the new humanist ways, growing in the society around them. But for many, the change in society did not come fast enough. The Jews were ready and willing but all they could see around them were people moving too slowly and not embracing the idea of Mensch as quickly as the Jews had. In the end, the Jews claimed the new humanity as their own, as having grown out of their religion, since the gentiles no longer were interested in it.

But was it Austrian culture the Jews assimilated in to? No, German culture. Most of the Jews originally had come from Germany and the Yiddish they spoke, if from the Eastern parts, was mostly mediaeval German. The Western Jews even spoke a closer version of German. Since the Jews were mostly merchants, they stood closer in relationship to the German middle classes then their Slav customers. Wherever one turned, the Jews were spreading German culture in the multi-cultural Monarchy. The  German culture the Jews were aspiring to was Beethoven, Goethe… but most of all “For the Jew Schiller was more real than actual Germans.” He spoke a language the Jews already understood and he was the ideal that they thought everyone would strive for one day, when educated enough. I guess this is the very sad part in history. An entire people thinking that a poet can symbolize an entire nation and its feelings. I have never read Schiller, but I can imagine that he painted a rosy picture far from the truth, and for all these people to be thus mislead, is just terrible when you think about it. When you read testimonies of people who stayed in Nazi Germany, they always say that they refused to believe that the Nazis would seriously hurt them. After all, they were the people of Goethe and Schiller. Well, they were not were they?

German culture the Jews were aspiring to was Beethoven, Goethe… but most of all “For the Jew Schiller was more real than actual Germans.” He spoke a language the Jews already understood and he was the ideal that they thought everyone would strive for one day, when educated enough. I guess this is the very sad part in history. An entire people thinking that a poet can symbolize an entire nation and its feelings. I have never read Schiller, but I can imagine that he painted a rosy picture far from the truth, and for all these people to be thus mislead, is just terrible when you think about it. When you read testimonies of people who stayed in Nazi Germany, they always say that they refused to believe that the Nazis would seriously hurt them. After all, they were the people of Goethe and Schiller. Well, they were not were they?

All the Jews in Austria in other words wanted to assimilate to the German North culture of Protestantism, which was completely contradictory to where they were actually living. In reactionary Catholic Austria, where the church was the enemy of education. When 1/4 of the Viennese Jews converted to Christianity, it was not to Catholicism but Protestantism, a small minority in the Monarchy. Before 1866, the Enlightened had hoped for a united Germany including Austria, but after that year, Austria was cut off as being hopeless and standing in the way for progress. The liberals and Jews, had to shift their loyalty to supporting the Habsburgs instead, looking upon them as the only thing German left in Austria. The Jews most fervently supported the idea of an Anschluss to the mother nation of Germany. They became full-blooded nationalists. The only thing which mattered now was to belong to the German Volk (people). Instead of joining in a universal human society, they would now join in a cultural nation. And this development took place to Jews in all other nations as well. The first generation of assimilated Jews in other words, strived to become part of Germany’s educated people, becoming rational individuals. The second generation just wanted to be part of the people.

But what happened in Austria, after they were cut off from the Reich, was that they became more German than the Germans. And while they adhered to the enlightened ideals, Germany now was abandoning them, for patriotic political systems. Austria did not yet know which route to take, with many wills pulling in different directions. Nationalism was not unproblematic for the Jews though. Aryans defended their superiority while Jews still struggled with overcoming themselves being Jewish. Soon nationalism grew in to being a blood alone movement, the only thing counting being racial qualities, and this of course did not suit the Jews. They did not belong in the nationalist Germany which became the ideal after 1885. That Germany was not that of Schiller and Goethe. Jews still loved everything German but had to look elsewhere for social and cultural change, since they now realized that the Germany they loved, had only existed in poetic dreams.

Beller devoted chapter 11 to Vienna. Finally! Vienna was considered the last German bastion. Teachers came from Germany. And as soon as Jews were allowed to, they flocked to Vienna. 1,3% lived there in 1857 and by 1890, 12% of the population was Jewish. Economy was a big reason for going there, but people with money flocked there as well to take advantage of all cultural luxuries available. Young Jews came to study and actually caused the first wave of anti-Semitism, since people thought too many Galician Jews came to study medicine. But many came to be free. Jews had not been allowed there between 1669-1848, so it was a city where you really could assimilate with no strong Jewish community holding you back.

Beller devoted chapter 11 to Vienna. Finally! Vienna was considered the last German bastion. Teachers came from Germany. And as soon as Jews were allowed to, they flocked to Vienna. 1,3% lived there in 1857 and by 1890, 12% of the population was Jewish. Economy was a big reason for going there, but people with money flocked there as well to take advantage of all cultural luxuries available. Young Jews came to study and actually caused the first wave of anti-Semitism, since people thought too many Galician Jews came to study medicine. But many came to be free. Jews had not been allowed there between 1669-1848, so it was a city where you really could assimilate with no strong Jewish community holding you back.

The Viennese Jews came from different places. Some had stayed from 1669, as tolerated Jews, but the majority came from Galicia, Hungary, Bohemia or Germany itself. The Bohemian Jews being very much like Protestants, looking at life as a task, working hard to accumulate wealth and being frugal. In 1883, Vienna no longer was seen as the forefront of liberalism. Too many Slavs had moved in. And the Catholic church was actually advocating illiteracy. Vienna was reverting back to its old ways. It was too multi-cultural and the countryside was more and more creating an Austrian identity. Austria was very much ruled by Church, Habsburgs and the high aristocracy, all working for the past not the future. Industry was designated to Hungary while Austria kept small craftsmen as the ideal. And the capital middle class, was Jewish. Unwanted since the aristocracy and artisans with their guilds worked fine without them. The bourgeoise in other words, was a foreign element which did not fit in to the Austrian structure of things, which compared to other countries, seems odd, since this class did nothing but grow in other countries and became a class to count with. In Vienna things remained status quo and Wiener Schmäh ruled, in other words, it was a place where “everyone lied in an attractive manner”.

The aristocracy lived for Carpe Diem, staying away from politics. Only getting in to music since it was so anti-political. Was it?? What about Wagner and his anti-Semitism? Was not that political if anything? The Austrian way of life came to boil down to one word, Gemütlichkeit, which means coziness, no serious thoughts. One hated education. And this Vienna was of course not the one the Jews had expected to arrive to. They arrived and became one nationality among many others. But they wanted to be absorbed in to the major group. Wealthy Jews found a way. They converted to Catholicism, adopted the appropriate lifestyle and tried their best at acquiring an aristocratic title. Aristocrats would only socialize with their own class. And of course as expected, they looked down at the money aristocracy, as the rich with new titles, were called. So, no true assimilation there.But the Jews who were not rich, what did they do?? First of all dress like everyone else. Try to be more Viennese than the Viennese. But as soon as you started to become successful, little things would give you away. Subtleties, social mistakes and you becoming painfully aware of being Jewish and that others might know. Perhaps an awareness that bother the Jew more than the people around him/her? The Jews became very loyal to the Habsburgs as mentioned above but not because of them being the rulers. No the Monarchy seemed to be the only thing that could guarantee the Jews liberties.

If one looks at Vienna, it was a city of contradictions. The press was liberal and supporting German ideals and the Protestant view of things. As part of all that, was the coffeehouses where like-minded could meet, discuss and read the newspapers or have business meetings. And business was very much the field of the Jews, of course. The anti-progress groups on the other hand, kept to the inns where hatred, prejudice and small-mindedness was the leading star. But the Jews had one more venue to meet and discuss things. They had imported the Berlin salon culture. What culture are we talking about really? Not the one of the senses but the one of the mind, the one which demanded education to understand. The educated class among the gentiles was of course part of this as well, but there was a difference. Culture was part of social standing to the latter, nothing else. According to Beller that is. He brings up the example of gentile girls being kept childlike intentionally while Jewish girls were taught to discuss books, poetry, nature and music at an early age. Gentile girls were supposed to just play mother and child games. I can not say that I agree with Beller. That it was only Jews who regarded culture as meaningful in itself and that the goal of life was to learn as much as possible. What does little girls prove? Nothing really! For heaven sake, we are talking about Victorian times here as well, where girls were supposed to remain untainted and innocent. That is a topic he avoids, since it would take away the point of his book. What he concludes from the Vienna chapter is that the Viennese culture fought against its surroundings, which threatened everything liberal.

Chapter 12 finally brings up the topic of Antisemitism. Because after 1895, the party in charge of Austria was an antisemitic one. Antisemitism has always been the strongest in central Europe and it is strange that Beller doesn’t at this time bring it up as a Catholic thing. From the earliest times, the church hated the Jews and indoctrinated the members of the Catholic faith to despise them. When legal oppression disappeared with the Enlightenment, the feelings did not. Antisemitism ran through the entire society and it needed little incitement to produce results. Being Jewish meant throughout the ages in Austria, that you could not really climb the social ladder.Unless you converted and this is what Jews did in the army and the legal profession. To convert was not easy tough. Family objected. Why should one have to sacrifice one’s heritage? All the same, 9 000 converted in Vienna between 1868-1903.

In the 1880s it was pointless to convert to get on though. Jew-hatred was by then too strong and Jewishness was seen as a psychological quality, something necessary to overcome. This is where I become confused. In one sentence it says that it was hopeless to do anything about it all. In another one, Wagner and Chamberlain said that it was quite possible. But by the 1880s German nationalists finally claimed that Jews could never become Germans because of race. In 1885 and 1896, the so-called Linz programme (note that Hitler was born outside Linz) claimed that Jews were born without honour and the people shutting them out, was the German intelligentsia, the ones the Jews in Vienna had admired the most. The place where you found the strongest advocates for this idea, was in the student body at the universities, among the future teachers and officials. Scary! The group that had previously stood for progress, freedom and reason, now stood for racial antisemitism. And for some strange reason, antisemitism worked as a unifying force, for all the different groups in the multi-cultural Vienna. They could all share in their hatred for the Jews. But everyone had a different idea of what a Jew really was. Finally it become up to each individual, to decide for themselves whom they regarded as Jewish.

How did it express itself? The cultural élite wrote of annihilation of Jews in the press. Jewish children had to be prepared to be beaten up in the streets. Adults faced economic boycott, not getting contracts and promotions. The Christian Social party did everything to cut off economic support for German ideas. Their plan was “to take every free institution, the influence of the middle classes, the political fruit of the progressive sciences, the moral effect of culture, and destroy them all.” Everything that had brought the Jews to Vienna. All that had voted liberal before had now turned against it, except the Jews. “Social intercourse between Jews and Christians came to a sudden stop.” How did the Jews react to the new isolation? Anger. Reverting in to their Jewish identity and religion. Jewish pride was re-discovered but this pride was not what one can imagine. It was in their liberal heritage. One response was Zionism, which started out with liberal, ethnic and traditional motives but soon lost its liberal motif. And the cultural élite was never interested in Zionism since they wanted to fight antisemitism not give in to it. Zionism meant surrendering to antisemitism, accepting that races are not compatible with each other but must live apart.

These anti-Zionists clung to the state which still gave them their rights and the monarch did happen to hate the new antisemitism. The economic boycotts did not work so things were regarded as not too bad after all, by these people. They did turn a blind eye to that they were strangers in their new home. But they could not do it for long. Gustav Mahler who held a prestigious post and who was Catholic said “I am rootless three times over: as a Bohemian among Austrians, as an Austrian among Germans, and as a Jew everywhere in the world.” Others thought differently. Freud thought the outsider role was alright. ” As a Jew, I was prepared to be in opposition and to renounce agreement with the ‘compact majority'” and many felt like him. They sought allies among other outsiders, like the working class and the socialists. Their motto became assimilate in the future and not in the present. Assimilation really meant to part with roots, to forget one’s origins and this made the Jews different once again in Viennese society, where everyone looked to the past, to heritage. While the Jews only looked to the future. They found that you could do this in nature and art. In nature, everyone could be home and with art you could reach fame. Fin de siècle was all about search for fame. Says Beller. Weird argument or statement! I thought all art was about stating something.

Culture became your background in this group, a society full of individualists who were aracial and asocial. But this fin de siècle became more and more Jewish, while the gentiles fled the group. The Jews assimilated in to a group that was already Jewish as it was. Why art world? It became the “secular version of the chosen people”. They were just searching for the truth in the different art forms. We are back at: Free will, you are responsible for your own actions, if this is not the case, morality will cease to exist. It seemed like at the time, the Jews were the only ones who wore these “moral spectacles”. It seems like the Jews in Vienna desperately looked for a purpose, when they no longer were allowed to be part of any group. And Beller’s discussion becomes just more and more “flummy”.

It was with relief that I reached the final chapter, this not being a light book to push through, nor one that one can read in a day or two. Beller claims that everyone was an outsider in the Habsburg Monarchy which lacked a natural center. He also claims that the Jewish presence was not an accidental one at all. One could claim that this was because most Jews had been unwelcome in the western part of Europe during earlier decades and were forced to settle in Eastern Europe. Where else then to go, when allowed to do so, than to the first capital available? Most of them also being citizens in the Habsburg Empire. But Beller of course claims that they went there to study and make something of themselves and that they chose Vienna because they loved everything German. Hm! There were German cities to go to if that was the case. Protestant cities which believed in the same things that the Jews now believed in. Being responsible for your own actions, working hard and educating yourself. Going to Vienna with its backwards striving Catholic church and aristocracy, still does not make any sense at all, afer reading this book. Except for the fact that they were citizens of that country.

What is interesting is how the Jews have always regarded education important no matter what social class or should I say no matter how much money one had in one’s wallet. And how the Gymnasiums suddenly had lots of Jews attending from the mid-1800s and onwards. Was it this constant hunger for learning, which made Vienna a center for learning and intellectualism and thoughts in 1900? That the entire fin de siècle, the cultural elite, was Jewish and as such could be isolated from the rest of society which by then wanted to strive backwards and not forwards, throwing over all liberal ideas and going for antisemitic nationalism instead to unite a fragmented nation. I don’t know. It seems like this is the result that Beller wanted and the result he therefore achieved. Making everyone in that group Jewish by guessing that their names are Jewish and generations since conversion, still counting them as Jews. Even if everyone knew a Jew back then who was involved in culture “work” it seems unlikely that gentiles were not involved as well. The Habsburg Empire was after all huge and cultural individuals did not really stay put, did they, but traveled around to learn more. Beller says that if Vienna was important in 1900, it was because it was on collision course with liberalism and this meaning being on collision course with the Jews. I feel that he has simplified things in order to set the Jews apart as being very special. Even if they are and were very prevalent in culture, they do not have monopoly on it. And we must not forget, that these Jews did NOT want to be regarded as Jews but just like Mensch. That never changed. They never let go of their liberal idealism. So why do we keep on going on an on about Jewishness? In itself, is it not being anti-Semitic.

I finished this book weeks ago, and I so wished that I would have enjoyed it. Especially since I had paid an awful £25 for it! An outrageous sum for such crap! I so much wish I could say that I understood the point of it and what it was trying to say because what I expected, was a description of 1867-1938 Vienna, but that is not at all what the book was about. It was plain theorizing throughout. Trying to prove a point that the only Vienna which mattered, was the Jewish intellectual group which shone like a light in a dark mediaeval part of Europe growing the more darker. Gentiles who made a difference must have been closet Jews otherwise Beller’s ideas will not hold up.

You must be logged in to post a comment.